Field Notes: A Guide for Parents of Young Workers in British Columbia

I was once a young worker, too. My first jobs were the usual patchwork of early adulthood: Tourism Counsellor at a visitor information centre, porter, dishwasher, waitress. Later, I became a Youth Coordinator, a Youth Stewardship Coordinator, and a Writing Tutor at university. I’ve been the one learning, the one training others, and now, as a Recreation Coordinator, I’m often the one hiring and mentoring young and new workers myself. The roles have changed, but the lesson hasn’t: if you don’t know your rights, someone else might decide them for you.

Know your rights, even when you are just starting out

Every worker in British Columbia is protected by the Employment Standards Act. Few young people ever read it, and few employers take the time to explain it.

Youth Stewardship Program in Gwaii Haanas.

WorkSafeBC defines a young worker as anyone under 25, and a new worker as someone new to a job or workplace. These are the people most likely to get hurt at work, not because they are careless, but because they are not given proper training, orientation, or support. Every young worker has the right to refuse unsafe work. That is not a suggestion. It is the law.

On Haida Gwaii, managing risk is part of the landscape. There are jobs that take people into the bush, along logging roads, across slippery docks, or into quiet facilities after hours. We are separated by long distances, unpredictable weather, and spotty cell service. The line between safe and unsafe is not always clear, so planning becomes everything. In a meeting once, the Visitor Safety Coordinator at Parks Canada reminded everyone in the room that emergency planning requires redundancy. One system is never enough. If the radio dies, the phone might still work. If no one answers, there should be a second contact. It is not about distrust, but about building backup into the culture of safety.

A 30 minute check in, like the Ministry of Forest uses for solo work, is considered best practice. Some organizations use Coastal Dispatch or satellite systems to keep track of workers in the field, logging each call until they return. Others rely on radio, text, or a simple check in and check out sheet on the office wall. It can be as basic as one person phoning another at the half hour mark to confirm they are okay.

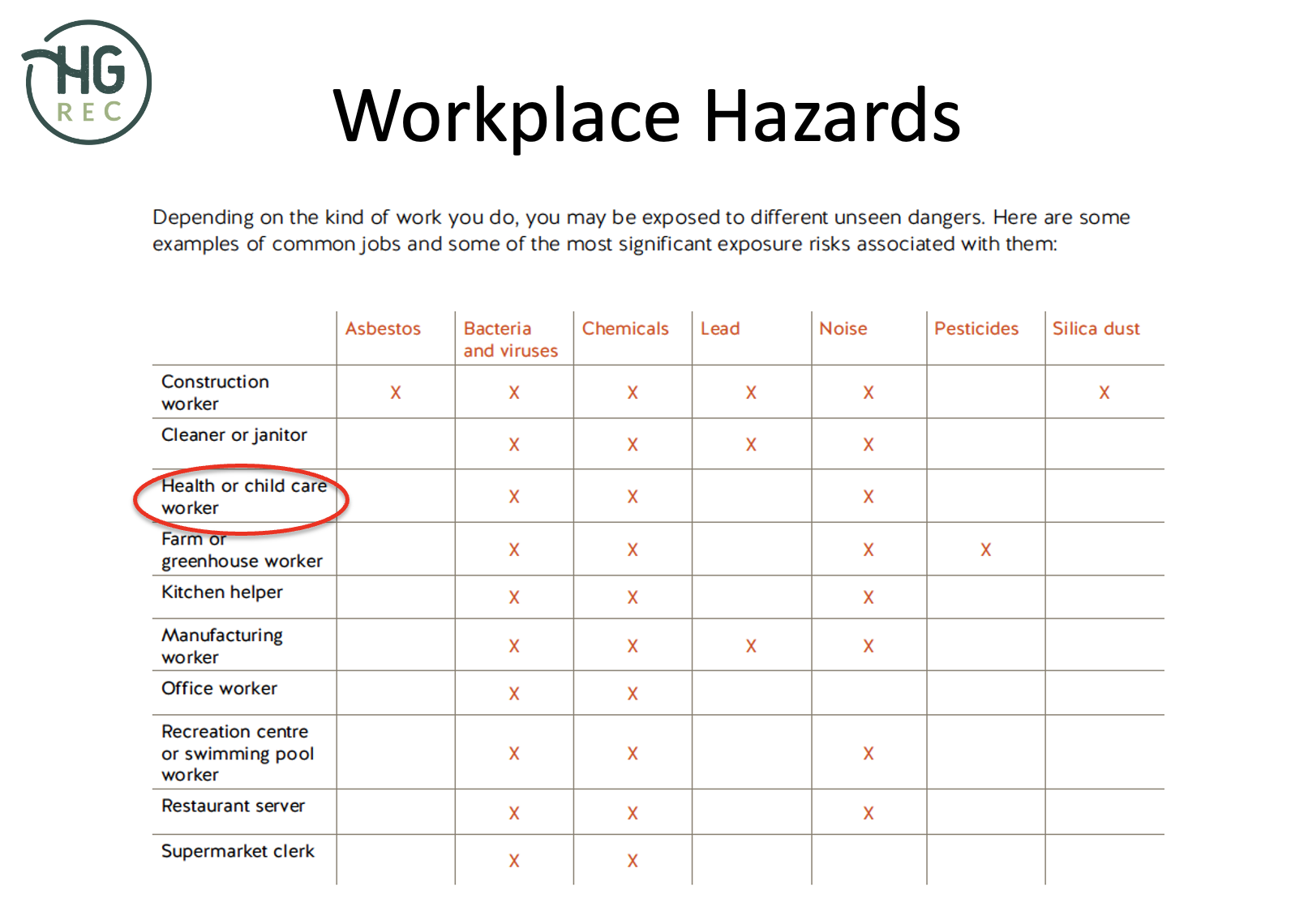

Parents should understand that on Haida Gwaii, and in most rural parts of BC, communication is not always reliable. A check-in app might fail when cell service drops. A text might never go through if someone is behind a hill or deep in the bush. A phone might die in cold weather. That’s why a good safety plan includes more than one way to make contact — for example, a radio plus a phone, or a radio plus a buddy system. Personal protective equipment (PPE) is important, along with WHIMIS safety sheets and training if you’re using any harmful substances on the worksite. In my work, we try to train youth to identify hazards before working with children, which include bacteria and viruses, potentially chemicals, and even noise (see image below).

Adapted from WorksafeBC: Identifying Hazards in the Workplace.

Encourage your kids to ask:

- Who do I check in with?

- How often?

- What happens if no one answers?

- What is my backup if my phone dies?

These questions are not about being overprotective. They teach responsibility. They remind youth that independence does not mean going it alone, and that safety is built through connection. Know who their supervisor is and how to contact them. The point is not to eliminate risk, because that is impossible here. The point is to acknowledge it and build systems that make it manageable.

Safety on Haida Gwaii looks like high visibility vests and knowing who will notice if you do not come back. It is about planning for it, staying connected, and recognizing that independence should never mean isolation.

The real cost of experience

When I was younger, I worked seasonal jobs where those hired from away had their housing, travel, and trucks paid for. Local youth like me lived at home, used our own vehicles, and covered our own costs. We were proud to have the job, but the gap was obvious. Some of us could drive a work vehicle during our shift, but once the day was done, it stayed parked at the yard. When we had to stay overnight in another community for an event or shift, meals were not always covered.

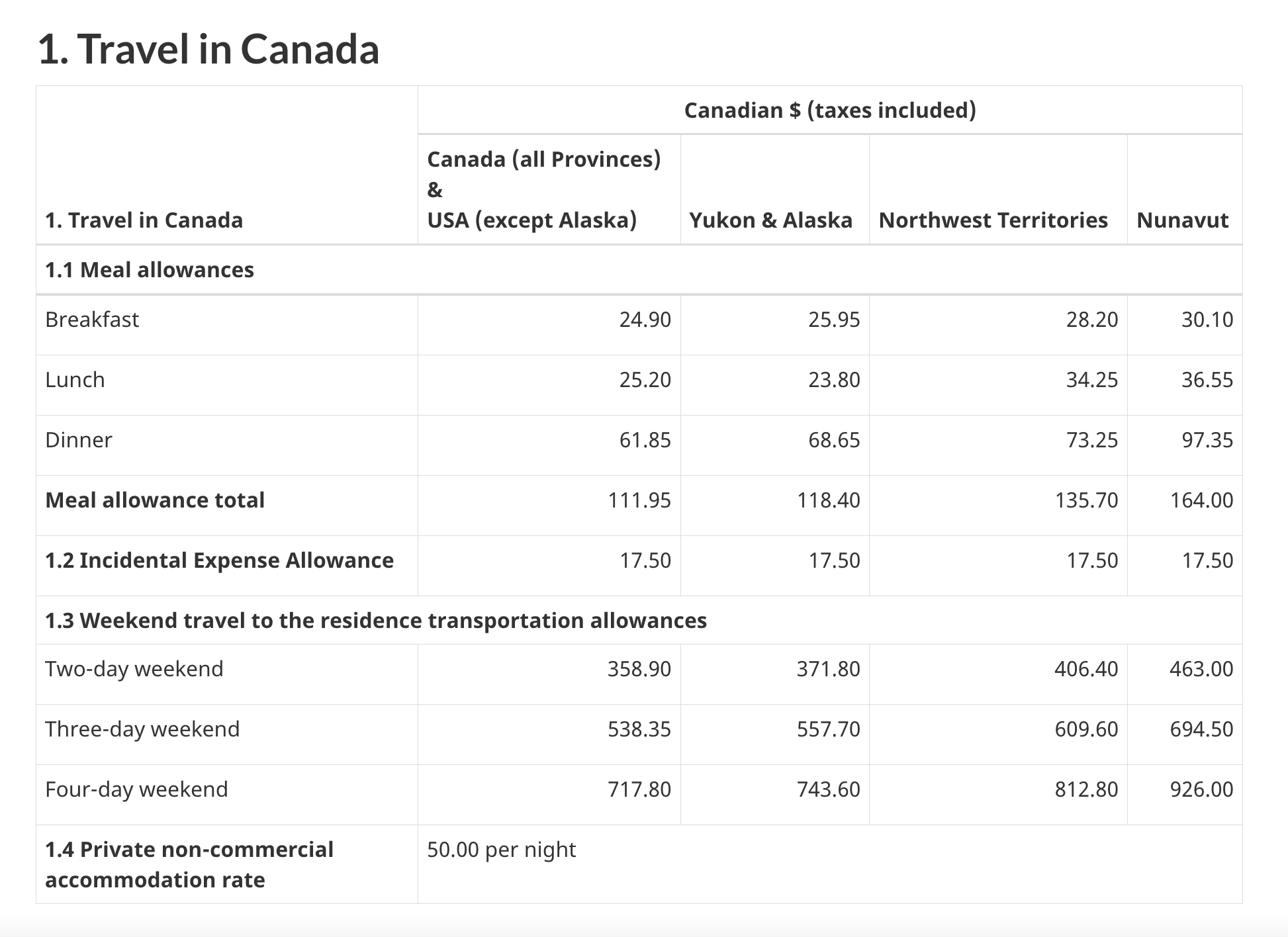

CRA Travel Per Diem Rates (2024).

It was subtle, but the message was clear. Our local labour was expected to stretch further for less. We were told we were gaining “experience,” while others were compensated for relocation, food, and time. For many young people on Haida Gwaii, that is still the reality of early employment. We get our start close to home, but the perks often go to those who come from elsewhere. It is not bitterness that I carry from that. It is awareness. Experience is important, but it should never come at the expense of fairness.

The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) publishes standard travel and mileage rates every year. These are used by federal employees and by many organizations to guide what is fair and non-taxable when workers travel or use their own vehicles for business.

As of 2025, the CRA mileage rates are:

$0.72 per kilometre for the first 5,000 kilometres driven in the provinces

$0.66 per kilometre for each additional kilometre

For the territories, rates increase by four cents to $0.76 and $0.70, respectively

To claim or reimburse mileage fairly, workers and employers must keep records. A proper logbook should include the date, destination, purpose of the trip, and distance covered, along with odometer readings at the start and end of the fiscal year. Receipts for fuel, maintenance, insurance, and registration must also be retained to support any deductions or reimbursements. Only the portion of driving directly related to earning income can be claimed; a reminder that commuting between home and a regular place of work is considered personal use.

Meal allowances are also clearly defined by the CRA. As of April 2024, those rates are $24.90 for breakfast, $25.20 for lunch, and $61.85 for dinner, for a total of $111.95 per full day of travel. These are standard federal rates that reflect the real cost of eating on the road. Many organizations will have their own rates, but always compare these to the CRA rates. And do ask why they are not following the CRA set rates as an organization, if you can.

When youth travel for work or attend training in another community, these are the minimums that should be considered. If meals or travel are not covered, those workers are effectively paying to work. That is not experience. That is subsidizing an employer.

When I hire young staff now, I think about those early years. I make sure they are not paying out of pocket for meals or travel when they represent our organization in another community. None of what I wasn’t paid was malicious - I think work to just know our rights helps us know what we’re entitled to. It’s important that we coach youth to know their rights and that work shouldn’t cost them. It sends a message that their time, energy, and safety matter. Fairness is not a luxury. It is the foundation that lets young people grow in their work without feeling like they are falling behind for showing up.

Mentorship is Part of the Job

When young people start working, parents can play an important role in helping them tell the difference between a good job and a careless one. A good workplace trains, supervises, and communicates. A careless one simply assigns tasks and leaves youth to figure things out alone.

Cape Fife Trail Marking, Youth Stewardship Program.

Under Canada Summer Jobs (CSJ), employers are required to provide mentorship and structured supervision. Each youth position must have a named supervisor, clear training, and a plan for feedback. If an employer does not meet these standards or if the work environment is unsafe, parents can contact CSJ. Complaints are reviewed, and repeated issues can affect that organization’s ability to receive funding again.

Parents and youth can verify whether a position is part of Canada Summer Jobs by checking the Youth Job Bank, an official Government of Canada site that lists all approved positions. These jobs are designed to offer safe, meaningful experience, not just wages.

Mentorship also means listening when young workers speak up. Last summer, our staff told us they could no longer manage a camp with children ranging from five to twelve years old. It was understandable. The difference in maturity and supervision needs between a five-year-old and a twelve-year-old is significant, and even with more staff, the pressure on them was too high. We adjusted the next round of camps to ages seven through twelve, and the result was night and day. There were far fewer incidents, and staff could focus on teaching, engaging, and building confidence.

That experience was a reminder that mentorship flows both ways. When youth feel safe to share their concerns and are heard, the whole workplace improves! Parents can support this by showing interest in what their child is learning, encouraging them to ask for guidance at work, and reminding them that speaking up about safety or fairness is always the right choice.

Good mentorship makes work more than just a summer job. It teaches young people that their time and effort matter, and that fairness and respect are part of every workplace that deserves them.

If you want more resources, you can check out WorksafeBC content, and have youth read and learn about BC Employment Standards.

Contractor or Employee: Why It Matters

When a young person is told they are a contractor, it can sound flexible and grown up. They get to set their own schedule, send invoices, and work independently. But unless they are truly running their own business, setting their own rates, and taking on multiple clients, they are likely an employee without the protections that once came standard.

Across Canada, secure full-time jobs have declined while contract and gig positions have increased. Statistics Canada reports that youth aged fifteen to twenty-four are about twice as likely as older adults to work in temporary or part-time roles. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives calls this a rise in “precarious employment” work that lacks predictability, benefits, or protection.

I experienced this firsthand as a young sole proprietor. Running my own business taught me independence and confidence, but it also cost me money. I waited months to be paid by large organizations while covering my own expenses. I learned that independence often shifts the financial risk onto the worker. Perhaps this makes sense if you have support and a higher level of financial literacy, but if you barely have an emergency fund, precarious work is even riskier.

Parents can help by encouraging their kids to ask key questions before accepting work. Will taxes be deducted? Are they covered if injured? How often will they be paid? If the employer sets the hours and provides the tools, that is usually employment, not contracting.

The loss of stable jobs is not the fault of young people. It reflects broader economic choices that favour flexibility over security. This is why youth need to be informed and to advocate for fair conditions. Awareness is the first step in protecting themselves and shaping a better future of work; one where flexibility does not replace fairness.

For the Employer: Meeting BC Employment Standards is the Floor, Not the Ceiling

If you want to be a successful employer for youth, mitigating harms and attracting talent, at minimum you must:

Pay them biweekly

Pay their expenses/reimbursements at least monthly (they have smaller cash flows!)

Use the “Show-Tell-Do” principle to help train them, not just hand them a manual

Create Emergency Response Plans for activities & make sure they are trained and process is followed

Be present in-person daily or weekly and provide constructive feedback

Provide personal protective equipment (like hard hats, high vis, etc.) or an allowance to purchase

Provide basic job training (First Aid, etc.)

Follow BC Employment Standards and know them well, and convey these lessons to staff:

Statutory holidays

In BC, a worker must be employed at least thirty days and have worked or earned wages on fifteen of the thirty days before the holiday to qualify for stat holiday pay.

Breaks

Every employee gets a thirty minute unpaid meal break after five hours. If they must stay on site during that time, it must be paid.

Split shifts

The total time from start to finish cannot exceed twelve hours. Employees must have enough rest between shifts.

Training time

All required training, even orientation, is considered paid work.

Uniforms and gear

If clothing or safety gear is required and not everyday wear, the employer must provide or reimburse it.

Pay periods

Employees must be paid at least twice per month. A pay statement must show hours worked, deductions, and vacation pay.

Overtime

Any hours beyond eight in a day or forty in a week must be paid at time and a half. Hours beyond twelve in a day must be paid at double time.

The workplaces that make the biggest difference for young people, especially in small towns, are the ones that go a little further.

That might mean offering a ride when transit is limited, showing up to help with setup instead of delegating, or taking time to check in after a long day. These small gestures model teamwork and teach that good leadership means pitching in, not standing back. Feedback matters too. Be honest but kind. Focus on growth, not blame. When something goes wrong, good supervisors own their part. It builds trust and teaches accountability.

Not every worker learns the same way. Neurodivergent youth may need structure, shorter shifts, or reminders to thrive. Under Canada Summer Jobs, a student who requests accommodation can work as few as twelve hours per week. Funding is not redacted if it’s declared and you ask for accommodation for the youth. Meeting people where they are is inclusive and it is good leadership.

Some simple tips:

Bring them a coffee or tea at work and help them tidy up at the end of a shift

Provide professional development opportunities that align with their career goals - you can’t keep them forever but you can help them grow!

Pick up and drop-off to work on occassion or provide a work vehicle if there is a barrier

Pay above minimum wage to attract and retain ($17.85 is actually not competitive on Haida Gwaii)

Parents Have a Role Too

Employers can do a lot to set young people up for success, but it starts at home. Parents can help by teaching basic communication, reliability, and teamwork. And, let your kids step into their own voice. It should be they, not you, who e-mails or brings in a resume or asks for a reference.

Encourage your kids to say when they will be late, to follow through on commitments, and to ask questions when they need help. These are small habits that build confidence and make a big difference once they start working. Help them practice showing up prepared, cleaning up after themselves, and taking pride in a job well done. Many camp-based jobs on Haida Gwaii depend on everyone pitching in — sweeping, setting up, moving equipment, or helping younger kids. When youth are comfortable helping with chores at home, they are better prepared to pick up the slack at work when the team needs it.

Parents, mentors, and supervisors all share the same goal. Together we teach young people that work is not just about earning a wage. It is about showing up for your community and learning how to take care of one another, in our homes, community, and in our workplaces. Kids can do tough stuff! Like hiking a mountain like kindergarteners have done at Agnes L. Mather’s school, or they can emcee an event like Wiija & Maurice did this fall for VIMFF Haida Gwaii, Best of the Fest. They’re our future leaders and they need us to show up for them.

Photo credit: Ivan Hughes, VIMFF